The Ancoats Artist (3)

Death and Legacy

Henry's three visits to London had proved a good investment and by 1831 his star was in the ascendant. He had exhibited paintings every year since 1827 in exhibitions at the Royal Manchester Institution, the British Academy and finally at the Royal Academy. While critics found occasional fault with his work, the overall reception was very positive and critics recognised improvements in his work and expressed a view that greater things might be expected of him. At a more practical level, his work was beginning to sell. We see prices of 30 to 50 Guineas mentioned and a record price of £130 guineas for his recent "masterwork" "The Recruit". His return from London was delayed by a few weeks due to the Duke of Devonshire wishing to meet with him - an indication of the circles in which his work was now appreciated.

Decline and Death

Henry arrived back in Manchester towards the end of July 1831. He appeared to be in somewhat low spirits, despite his growing success, the cause of his depression clearly being a decline in his health. He nevertheless continued to work through the remainder of the year. As the new year opened, it was clear that he was seriously unwell. His legs had swollen and he was apparently having some difficulty walking as he had suggested buying a pony on which to get around the town.

When the end came, it came quickly, though seemingly painlessly. On the evening of 12 January 1832 he seemed to have a premonition of his death, remarking to Mrs. Green "Aunt, if anything should happen to me, take care of my pencil sketches, for they are valuable". His final wods were to his sister as he retired for the night "Good night my sister, I hope all will be well. It is in God's hands". The next morning, he could not be woken. A physician was called, but nothing could be done. He half-opened his eyes, placed his hand on his heart and expired.

Following his death, friends visited to pay their respects. The first of these was his long-term friend and fellow artist Michael Pease Calvert. Another visitor would undoubtedly have been his friend Maria Jane Jewsbury, who quickly penned an obituary, which was published in The Athenaeum within a week of his death. One of the visitors who today we might regard as rather macabre was his old friend and fellow Manchester artist William Bradley. Bradley had painted a portrait of Henry (today in Salford Art Gallery) but on this occasion took a post mortem cast of Henry's face, which was to be used by "Mr. Stephens" (his precise identity remains unknown) in sculpting a bust of the artist, the present whereabouts of which, if it was ever completed, are unknown.

Henry died intestate. letters of Administration were issued to Henry's brother, John Mitchell Liverseege, his father having renounced his rights as administrator. His effects were valued for probate at "Under £200", a sum which would equate to some £30,000 today; by no means a fortune, but a comfortable sum.

The Funeral

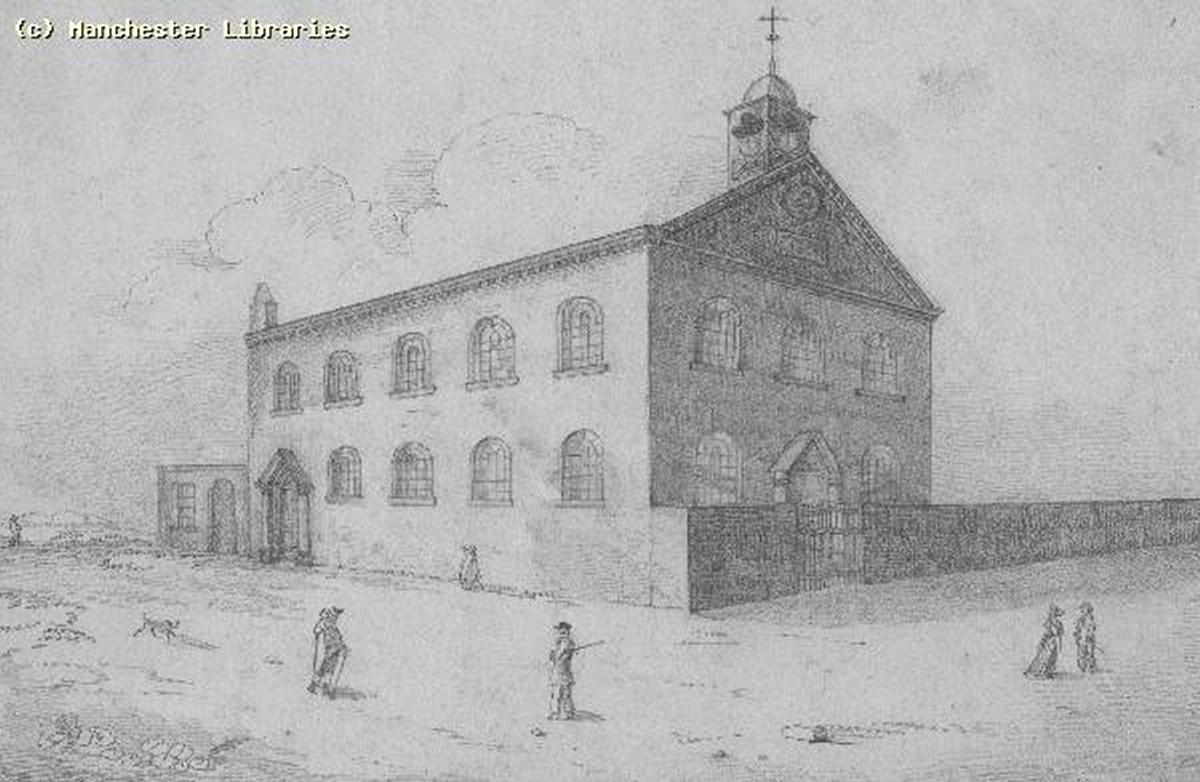

Henry was buried on 19 January 1832 in the churchyard of St. Luke's church in Chorlton-on-Medlock. He was interred in the family grave of his mother's family, the Mitchells and the simple epitaph "Henry LIVERSEEGE died 13th January 1832 aged 29 years" added to the memorials for his grandparents and mother. The funeral was attended by Henry's many friends in Manchester and two of his artist friends came up from London for the funeral. These were Alfred Gomersal Vickers, who would the following year marry Henry's sister Mary, and Mr. Stephens; presumably the family had written to them immediately following Henry's death for them to receive sufficient notification and get to Manchester within six days of the death.

St Luke's Church, 1820, Michael Pease Calvert

(Manchester Libraries)

Obituaries

What may be considered the definitive obituary was published in the grandly titled "Library of fine Arts or Repertory of Painting, Sculpture, Architectire and Engraving" for the year 1832. We may measure the interest which Henry had generated in the artistic world by the sheer length of the obituary, which runs to ten pages, plus a further six pages under the heading "The Last Days of Henry Liverseege". The article opens with the proclamation:

"Within comparatively but a few years, death has deprived the English School of Art of four of her most promising students; men who bade fair by the individual originality and power of their genius to rival the great and illustrious masters of old; and with one or two exceptions, to surpass even all who preceded them, or were their contemporaries, of their own country".

The author goes on to mention the recent deaths of Richard Parkes Bonington and Thomas Girtin, who today still are well-remembered, and in 1819 of George Henry Harlow, who is less so. All of these, like Henry, had died young, Bonington aged 27, Girtin 29 and Harlow 32.

It is clear that the unnamed author was either a close friend of Henry or had access to friends who had known him well. Henry's childhood is described in some detail, as is his early career in portraiture before he came to London and thereafter, his artistic development, growing reputation and increasing commercial success are set out at length. The author, who is otherwise nothing but complimentary regarding Henry's work, points out a single failing, common to several of his paintings; that he makes his figures too long. This is undoubtedly true. Had he succeeded in admission to the Poyal Academy School, perhaps it is one which might have been quickly remedied. The same obituary appeared unchanged in the 1833 edition of the Annual Biography and Obituary.

A short, but possibly independent obituary appeared in "The Day", a "journal of literature, fine arts, fashion, etc.", published in Glasgow in 1832. This describes Henry as "...this young and much admired artist".

The next year, 1834, saw the inclusion of a thirteen page memorial to Henry in Allan Cunnihgham's "Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters and Sculptors". This, by its own admission, draws both on Miss Jewsbury's original obituary and on that which appeared in the Library of fine Arts.

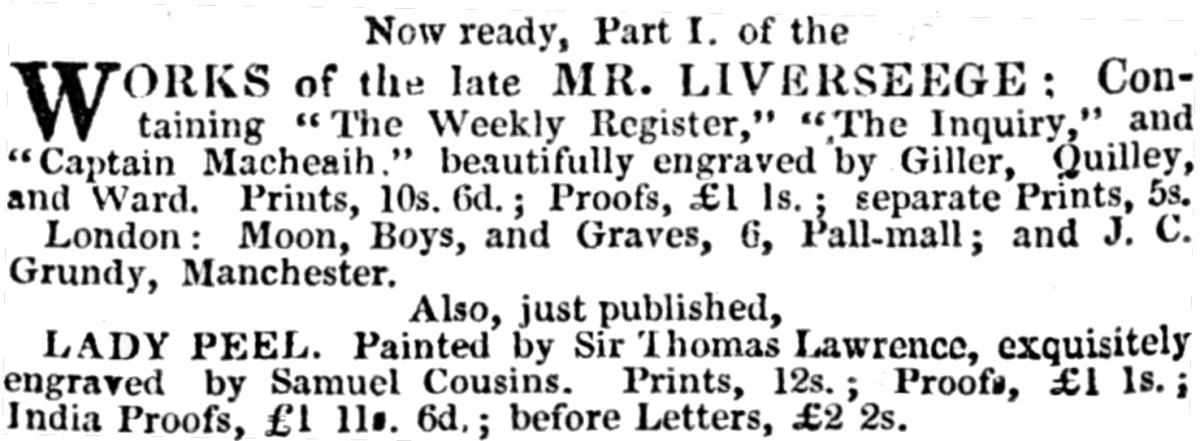

As early as 10 March 1832, just two months after the artist's death, the Manchester printseller Samuel Clowes Grundy, in association with the engravers Moon, Boys and Graves announced their intention to make engravings from the most important of Liverseege's paintings and were soliciting owners to come forward to offer their works for reproduction. Six months later, the first three prints were on offer individually for 5 shillings or as a set priced at 10s 6d or 1 Guinea for proof copies, of which 100 were to be offered, most of which were said to have been subscribed for. These prices would equate to around£35, £75 and £150 today. Eleven further batches were produced over the next two years until the complete series were publushed as a bound volume.

In association with the engravings, Liverseege's old friend, the poet and engraver Charles Swain, wrote a biography of the artist. This was initially offered as a atand-alone pamphlet, but copies were later bound with the reprint of the collected engravings.

There was a suggestion in the Manchester Courier of 21 Mar 1835 that a memorial was to be installed at the (Manchester) Royal Institution. This was to tahe the form of a marble panel depicting in relief, three of his paintings. This was to be surmounted by a portrait bust of Liverseege also in marble, possibly the same bust which was to be sculpted by "Mr. Stephens". This memorial seems not to have come to fruition. It would be another three decades before a proper memorial was erected.

Finally, a memorial

Henry slipped from public memory as the decades passed, though several of his works were exhibited at the Art Treasures Exhibition held in Manchester in 1857. But on 8 Feb 1864, a letter appeared in the Manchester Guardian under the initials "R.W.P", a thinly-disguised Richard Wright Procter. Procter, in addition to working as a barber, was also what we would today call a local historian and one familiar with Henry Liverseege, who had died when Procter was about fifteen years old. Procter's concern was that St. Luke's church was being rebuilt and Henry's grave was at risk of disappearing. The letter raised awareness and once the new church was completed, Henry's grave was incorporated, with several others, within the larger building, where they ended up under Pew No. 51. A simple brass plate was fixed to the floor bearing the simple inscription "Beneath this spot lies the body of Henry Liverseege" .

Procter's letter also caught the attention of Guardian's editor, John Edward Taylor, who expressed disappointment that there was no proper memorial to Liverseege and invited readers to subscribe towards erecting one. Although nothing seems to have been published about the response, sufficient was raised to commission the sculptor Marshall Ward to create a wall tablet. The memorial is carved in white marble and shows a female figure depicting the muse of painting (there is, in truth, no muse specifically assigned to painters) laying a wreath on a sarcophagus on which is carved a medallion portrait of the artist. The inscription reads:

Henry Liverseege, painter, born at Manchester September 4, 1803*, where he died January 13, 1832 is buried in this church. He cultivated his innate love of painting in defiance of adverse circumstances and a weakly frame. Life was to him a school of earnest study of his art in the subjects of romance and humour, to which his genius inclined. Death overtook him as he passed from scholar into master. Some of his townsmen, who, in the pictures he has left, recognise his genius, and lament the death that left such promise unfulfilled, have raised this stone to his memory. June 1865.

* This should read 1802. The error is discussed in part 1 of this blog.

St. Luke's church closed in 1962 and was subsequently demolished. Fortunately, the value of the Liverseege memorial was recognised and it was rescued and today is kept safely in the store room of Manchester Art Gallery. To my knowledge, it has never been on display.

Remenbered - and then forgotten

There was something of a revival of interest in Liverseege following the erection of the memorial. Samuel grundy re-published the volume of engravings and added a memorial of the artist's life written by his contemporary and former friend, Charles Swain. Another of Henry's old friends, George Richardson, penned an article which appeared in two parts in Ben Brierley's Journal for 19 Jul. and 1 Aug 1874.

Local historian Thomas Swindells included a whole article on Liverseege in his series of articles about Manchester history which originally appeared in the Manchester Guardian but which he later published in five bound volumes during 1907/8.

A final biography was published in 1920 in the papers of the Manchester Literary Club for that year. The article was written by local historian Walter Butterworth but appears to be based on accounts published previously rather than on original research.

Ars Longa Vita Brevis

Nearly two hundred years after his death, Liverseege is all but forgotten. But if his name is no longer remembered, even in his home city, his work lives on. Manchester Art gallery and The Whitworth each hold several of his paintings, watercolours and drawings, though sadly seldom on display. Works can also be found in galleries at Salford, Bolton, Preston, Stalybridge, Hereford and Worcester. The National Army Museum owns the original version of his most important painting "The Recruit". One of his watercolours, "A Lady Reclining", is owned by the Wichita Art Museum in Kansas, USA and a copy of his "Don Quixote in his Study" by the National Gallery of Canada. Some 61 works can be accounted for in public collections.

A similar number are known to be held in private collections and have appeared in recent auction catalogues. While most have been sold in the UK, some have appeared in overseas auctions including in Austria, Denmark and Germany, with several sold in the USA. Liverseege's work commands only modest prices at auction, with the highest price achieved in recent sales being little more than £2,000.

Finally, there is the remainder of the 214 works which I have so far identified of which nothing has been seen in the past century. Possibly they are in private collections or even in gallery collections, but lacking attribution (Liverseege did not always sign his work). Previously unknown works continue to reappear, so the number of known works may yet increase.

As we approach the bi-centenary of Henry Liverseege's death, it would be nice to think that Manchester Art Gallery may mark this anniversary in 2032 with an exhibition of his works. Perhaps we will see this long-forgotten artist return to the public eye.

- Hits: 139