Transcript from : 'The Annals of Manchester'

ed. William E.A. Axon, Pub. 1886

INTRODUCTION.

MANCHESTER, the great centre of the cotton manufacture, is a corporate and Parliamentary borough, and was elevated to the dignity of a city in1847, by being constituted the see of a bishop, and by, royal proclamation in 1858. It is situated on the river Irwell, in the hundred of Salford, and county of Lancaster, and is distant from London 188 miles by the London and North-Western Railway, 189 by the Midland, 188¾ by the Great Northern, and 31½ from the port of Liverpool. According to the census of 1881, the municipal borough of Manchester contained 341,414 inhabitants, and the Parliamentary borough, which includes the townships of Harpurhey, Newton, Bradford, and Beswick, contained 393,585. In 1885 the city boundary was extended to include Rusholme, Bradford, and Harpurhey. and the population of the municipal borough was thus raised to 373,583, and of the Parliamentary borough to 406,82-3. The limits of the municipal and Parliamentary borough of Salford are identical, and the population at the census of 1881 was 176,235.

The following outline of the history of the city is condensed from an article contributed to the Encyclopedia Britannica by the editor of this volume :-

Very little is known with certainty of the early history of Manchester. It has, indeed, been conjectured, and with some probability, that at Castlefleld there was a British fortress, which was afterwards taken possession of by Agricola. It is, at all events, certain that a Roman station of some importance existed in this locality, and a fragment of the wall still exists. The period succeeding the Roman occupation is for some time legendary. As late as the 17th century there was a floating tradition that Tarquin, an enemy of King Arthur, kept the castle of Manchester, and was killed by Launcelot of the Lake. Early mention of the town, in authentic annals, is scanty. It was probably one of the scenes of the missionary preaching of Paulinus; and it is said (though by a chronicler of comparatively late date) to have been the residence of Ina, King of Wessex, and his queen Ethelberga, after he had defeated Ivor, somewhere about the year 689. Nearly the only point of certainty in its history before the Conquest is that it suffered greatly from the devastations of the Danes, and that in 923 Edward, who was then at Thelwall, near Warrington, sent a number of his Mercian troops to repair and garrison it. In Domesday Book, Manchester, Salford, Rochdale, and Radcliffe are the only places named in South-East Lancashire, a district now covered by populous towns. Large portions of it were then forest, wood, and waste lands. Twenty-one thanes held the manor of Salford among them. The church of St. Mary and the church of St. Michael, in Manchester, are both named in Domesday and some difficulty has arisen as to their proper identification. Most antiquaries have considered that the passage refers to the town only, whilst others think it relates to the parish, and that, while St. Mary's is the present Manchester Cathedral, St. Michael's would be the present parish church of Ashton-under-Lyne. Manchester and Salford are so closely allied that it is impossible to disassociate their history.

Salford received a charter from Ranulph de Blundeville, in the reign of Henry III., constituting it a free borough, and Manchester, in 1301, received a similar warrant of municipal liberties and privileges, from its baron, Thomas Greeley, a descendant of one to whom the manor had been given by Roger of Poictou, who was created by William the Conqueror lord of all the land between the rivers Mersey and Ribble. The Gresleys were succeeded by the De la Warres, the last of whom was educated for the priesthood, and became rector of the town. To avoid the evil of a non-resident clergy, he made considerable additions to the lands of the church, in order that it might be endowed as a collegiate institution. A sacred guild was thus formed, whose members were bound to perform the necessary services of the parish church, and to whom the old baronial hall was granted as a place of residence. The manorial rights passed to Sir Reginald West, the son of Joan Greslet, and he was summoned to Parliament as Baron de la Warre. The West family, in 1579, sold the manorial rights for £3,000 to John Lacy, who, in 1596, resold them to Sir Nicholas Mosley, whose descendants enjoyed the emoluments and profits derived from them until 1845, when they were purchased by the Town Council of Manchester for £200,000. The lord of the manor had the right to tax and toll all articles brought for sale into the market of the town; but, though the inhabitants were thus to a large extent taxed for the benefit of one individual, they had a far greater amount of local self-government than might have been supposed, and the Court Leet, which was the governing body of the town, had, though doubtless in a somewhat rudimentary form, nearly all the powers and functions now possessed by municipal corporations. This court had not only control over the watching and watering of the town, the regulation of the water supply, and the cleaning of the streets, but also had power, which at times was used freely, of lnterfering with what would now be considered the private liberty of their fellow-citizens.

Some of the regulations adopted, and presumably enforced, sound grotesque at the present day. Under the protection of the barons the town appears to have steadily increased in prosperity, and it early became an important seat of the textile manufactures. Fulling mills were at work in the 13th century; and documentary evidence exists to show that woollen manufactures were carried on in Ancoats at that period. An Act passed in the reign of Edward VI. regulates the length of cottons called Manchester, Lancashire, and Cheshire cottons. These, notwithstanding their name, were probably all woollen textures. It is thought that some of the Flemish weavers who were introduced into England by Queen Philippa of Hainault were settled at Manchester; and Fuller has given an exceedingly quaint and picturesque description of the manner in which these artisans were welcomed by the inhabitants of the country they were about to enrich with a new industry, one which, in after centuries, has become perhaps the most important industry in the country. The Flemish weavers were, in all probability, reinforced by religious refugees from the Low Countries. Leland, writing in 1638, decribes Manchester as the “fairest, best builded, quickest, and most populous town of Lancashire.” In 1641 we hear of the Manchester people purchasing linen yarn from the Irish, weaving it, and returning it for sale in a finished state. They also brought cotton wool from Smyrna to work into fustians and dimities. The right of sanctuary had been granted to the town, but this was found to be so detrimental to its industrial pursuits that, after very brief experience, the privilege was taken away.

The college of Manchester was dissolved in 1547, but was re-founded in Mary's reign. Under her successor the town became the head-quarters of the commission for establishing the reformed religion. In the civil wars the town was besieged by the Royalists under Lord Strange, but was successfully defended by the inhabitants under the command of a German soldier of fortune, Colonel Rosworm, who complained with some bitterness of their ingratitnde to him. An earlier affray between the Puritans and some of Lord Strange's followers is said to have occasioned the shedding of the first blood in the disastrous struggle between the King and Parliament. The year 1689 witnessed that strange episode, the trial of those concerned in the so-called Lancashire plot, which ended in the triumphant acquittal of the supposed Jacobites. That the district really contained many ardent sympathisers with the Stuarts was, however, shown in the rising of 1715, when the clergy ranged themselves to a large extent on the side of the Pretender, and was still more clearly shown in the rebellion of 1745, when the town was taken possession of by Prince Charles Edward Stuart, and a regiment, known afterwards as the Manchester regiment, was formed and placed under the command of Colonel Francis Townley. In the fatal retreat of the Stuart troops the Manchester contingent was left to garrison Carlisle, and surrendered to the Duke of Cumberland. The officers were taken to London, where they were tried for high treason and beheaded on Kennington Common.

The variations of political action in Manchester had been exceedingly well marked. In the 16th century, although it produced both Catholic and Protestant martyrs, it was earnestly in favour of the reformed faith, and in the succeeding century it became indeed a stronghold of Puritanism. Yet the descendants of the Roundheads, who defeated the army of Charles I., were Jacobite in their sympathies, and by the latter half of the 18th century had become imbued with the aggressive form of patriotic sentiment known as Anti-Jacobinism, which showed itself chiefly in dislike of reform and reformers of every description. A change was, however, imminent. The distress caused by war and taxation, towards the end of the last and the beginning of the present century, led to bitter discontent, and the anomalies existing in the Parliamentary system of representation afforded only too fair an object of attack. While single individuals in some portions of the country, had the power to return members of Parliament for their pocket boroughs, great towns like Manchester were entirely without representation. The injudicious conduct of the authorities, also, led to an increase in the bitterness with which the working classes regarded the condition of society in which they found themselves compelled to toil with very little profit to themselves. Their expressions of discontent, instead of being wisely regarded as symptoms of disease in the body politic, were looked upon as crimes, and the severest efforts were made to repress all expression of dissatisfaction. This foolish policy of the authorities reached its culmination in the affair of Peterloo, which may be regarded as the starting point of the modern Reform agitation. This was in 1819, when an immense crowd assembled on St. Peter's Fields (now covered by the Free Trade Hall and warehouses) to petition Parliament for a redress in their grievances. The authorities had the Riot Act read, but in such manner as to be quite unheard by the mass of the people, and drunken yeomanry cavalry were then turned loose upon the unresisting mass of spectators. The yeomanry appear to have used their sabres somewhat freely; several people were killed and many more injured, and although the magistrates received the thanks of the Prince Regent and the ministry, their conduct excited the deepest indignation throughout the entire country.

Naturally enough, the Manchester politicians took an important part in the reform agitation, and when the Act of 1832 was passed, the town sent as its representatives the Right Hon. C. P. Thomson, Vice-President of the Board of Trade, and Mr. Mark Philips. With one notable exception, this was the first time that Manchester had been represented in Parliament since its barons had seats in the House of Peers in the earlier centuries. In 1654 Mr. Charles Worsley and in 1666 Mr. R. Radcliffe were nominated to represent it in Cromwell's Parliaments. Worsley was a man of great ability, and must ever have a conspicuous place in history as the man who carried out the injunction of the Protector to “remove that bauble,” the mace of the House of Commons. The agitation for the repeal of the corn-laws had its head-quarters at Manchester, and the success which attended it, not less than the active interest taken by its inhabitants in public questions, has made the city the home of various projects of reform. The “United Kingdom Alliance for the Suppression of the Liquor Traffic” was founded there in 1853 and during the continuance of the American war the adherents both of the North and of the South deemed it desirable to have organisations to influence public opinion in favour of their respective causes.

A charter of incorporation was granted in 1838; a bishop was appointed in 1847; and the town became a city in 1853. The Lancashire cotton famine, caused by the civil war in America, produced much distress in the Manchester district, and led to a national movement to help the starving operatives. The relief operations then organised are amongst the most remarkable efforts of modern philanthropy.

The spinning of cotton and the manufacture of various fabrics from that article are the staple of the Manchester district. There are also calico-printing works, in a wide circuit round Manchester, of great magnitude, and the warehouses established in the city in connection therewith are of corresponding extent; while the bleach and dye works, for miles round, furnish employment to numerous hands. The manufacture of an infinite variety of articles comprised in the general term of "smallwares” engages a large amount of capital, and many of the mills are of large dimensions. Ironfounding and the manufacture of stationary and locomotive steam engines, together with machine and tool making, are branches of great importance, employing immense power and expenditure. Many chemical works are on an extensive scale, and in the vicinity are paper mills. The merchants and manufacturers of Manchester have commercial relations with all parts of the world.

Manchester contains some fine public buildings, the most noteworthy being the Royal Exchange, Assize Courts, Royal Infirmary, Free Trade Hall. Royal Institution, the Town Hall, the Owens College, and the Post Office. The new Town Hall is one of the most spacious and elegant structures in Europe, and is probably the largest in the world devoted to civic purposes. Besides public edifices, there are many warehouses of gigantic size, foremost among which stands the magnificent warehouse of Messrs. S. and J. Watts. Many new streets have been formed of late years, and others widened for the immense traffic constantly passing along them. Nearly in the centre of the city is Albert Square, in which stands the new Town Hall and the memorial erected to the late Prince Consort. Deansgate, an ancient thoroughfare of many centuries’ existence, has been transformed into a broad and handsome street.

The charitable institutions of the city are numerous, affording relief and consolation to the poor and indigent. The educational machinery of Manchester and Salford ranges from excellent elementary schools to the Victoria University, empowered to grant degrees alike to men and women. Schools for the Deaf and Dumb and an Asylum for the Blind are likewise provided; whilst the foundations of Bishop Oldham, Humphrey Chetham, and Benjamin Nicholle remain as monuments worthy of imitation.

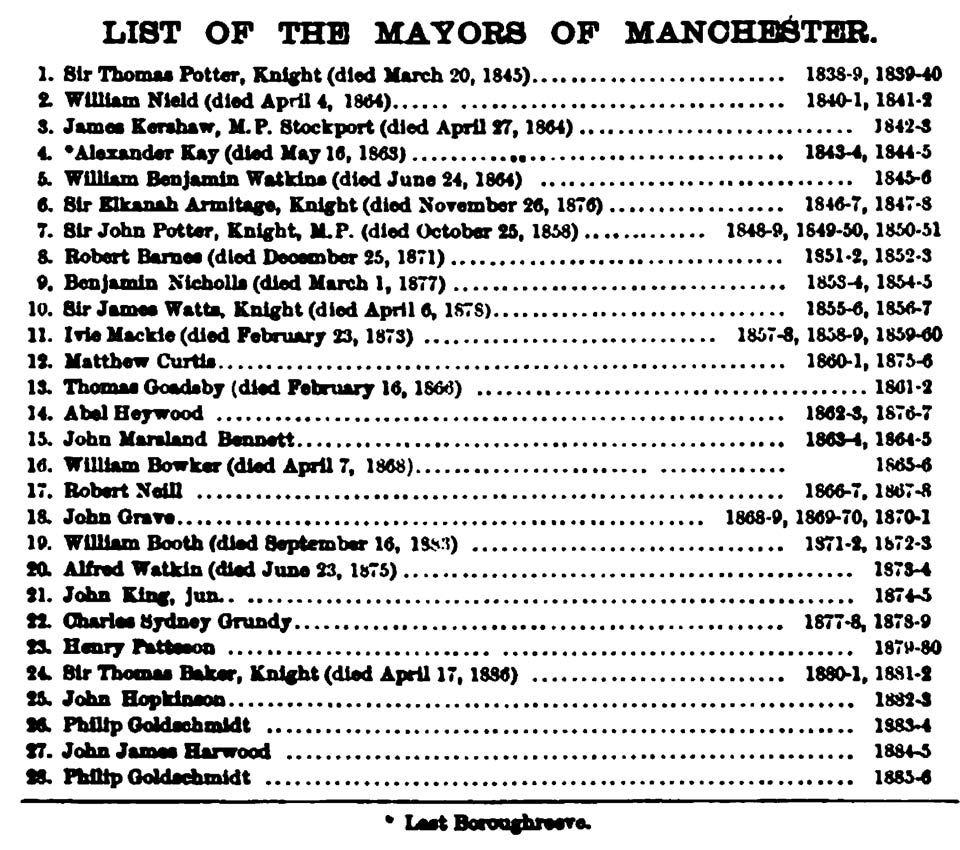

The government of Manchester, previous to the charter of incorporation being granted, was vested in a boroughreeve, two constables, and other officers, elected or appointed at the Court Lest of the Lord of the Manor. The corporate body, under the municipal charter, consisted of a mayor, fifteen alderman, and forty-eight councillors. This number has increased, since the incorporation of Rusholme, Bradford, and Harpurhey into the city, to nineteen alderman and fifty-seven councillors. The first election took place on the 14th December, 1838, and on the 15th Mr. Thomas Potter, afterwards knighted, was elected to the civic chair, and the following year re-elected. A stipendiary magistrate sits daily at the City Court, Minshull Street, for the disposing of petty offences, or committal to the sessions or assizes of more serious offenders.

Salford also has a stipendiary magistrate, who sits at the Town Hall. Assizes are held thrice during the year, and sessions every six weeks.

.pdf List of Manchester Borough Reeves from 1552 - 1846, HERE