The Ancoats Artist (1)

Becoming an Artist

As the eighteenth century drew to a close, Manchester was already growing rapidly on the back of the mechanisation of cotton spinning and weaving. The native population of what was then a small town was grossly inadequate to service the needs of this expanding industry and families and individuals were being drawn into the town from far afield on the promise of secure employment. Among these incomers was Edmund Liverseege.

Family Background

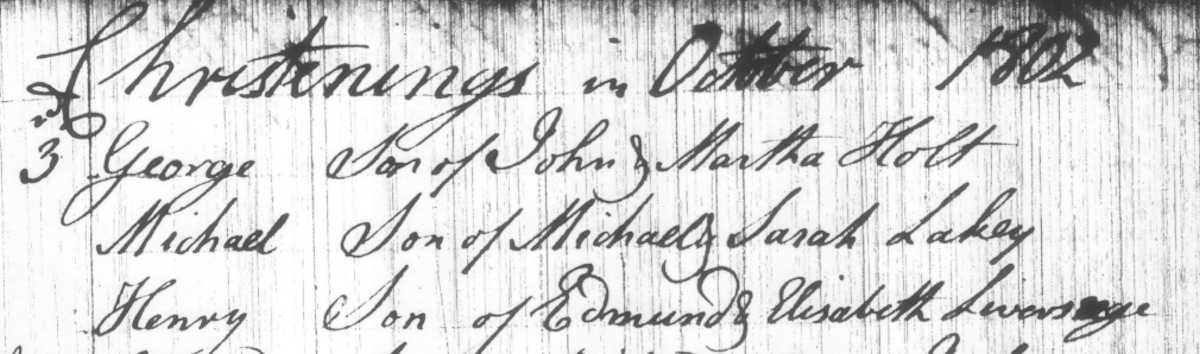

Edmund was born at Aberford in Yorkshire and baptised there on 30 December 1774. He was a joiner by trade and probably considered the prospect of secure employment in Manchester to be much better than in the village where he was born. There is no record of when he arrived in Manchester but it was probably some time in the 1790s. Certainly by 1801 he was feeling sufficiently well-established to marry and raise a family; he married Elizabeth Michell, herself an "incomer", at the Collegiate Church on 15 September of that year. They lived in Shepley Street, between Piccadilly and Minshull Street in Ancoats, whare their first child, a son they named Henry, was born, barely a year later on 4 September 1802. He was baptised at the Collegiate Church a month later on 3 October. Henry would remain an only child until he was nearly six years old when his brother John Mitchell was born. After another long wait, they were joined by a sister Mary in 1815 and finally by another brother, Edmund, named after his grandfather and father, in 1817.

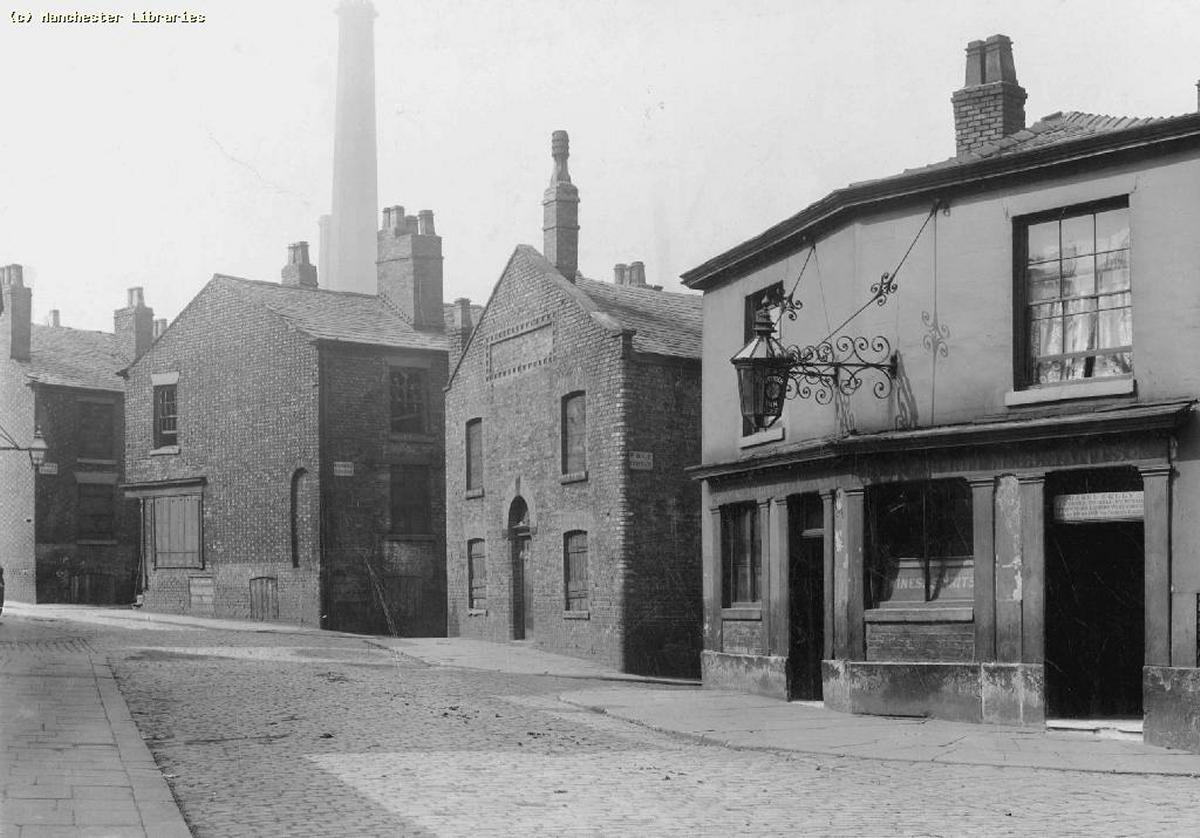

Shepley Street c1920

(Manchester Local Image Collection)

About Henry's Birth date

Before we continue with Henry's story, a word is necessary about his birth date. This has been widely mis-recorded as having been in 1803. The confusion stems from a simple mathematical error. When he was buried on 19 January 1832, the register recorded his age as 29. Simple mathematics 1832-29 produces a birth date of 1803. However, common sense dictates that it could have been any date between 20 January 1802 and 18 January 1803. The error arose when a memorial was erected three decades after his death inscribed "Henry Liverseege, painter, born at Manchester September 4, 1803 ...". Whoever composed the memorial clearly knew his birth day and month but failed to calculate that this must have been in the year 1802. This error has echoed down to the present day and dates of 1803-1832 widely attached to his name when his works come on the market. The Collegiate Church register clearly shows his baptism on 3 October 1802.

A Sickly Child

Henry's arrival must have brought Edmind and Elizabeth mixed feelings; the joy of their first-born, but overshadowed by the disabilities which would impede him throughout his short life. His most visible disability was scoliosis, curvature of the spine, which resulted in his left shoulder being noticeably higher than the right, but his most troublesome disability was asthma, which afflicted him from his earliest years. As a child, he did not thrive as other children and might perhaps best be described as "delicate". We must fast-forward to his twenties to get some idea of how he must have been as a child.

He was small, spare, pale, frail; slightly deformed, his left .shoulder being higher than the right. His chest was prominent, probably from curvature of the spine. At twenty-five he weighed but seventy-five pounds. One lung was useless, and he had throughout to struggle against feeble health. (Walter Butterworth)

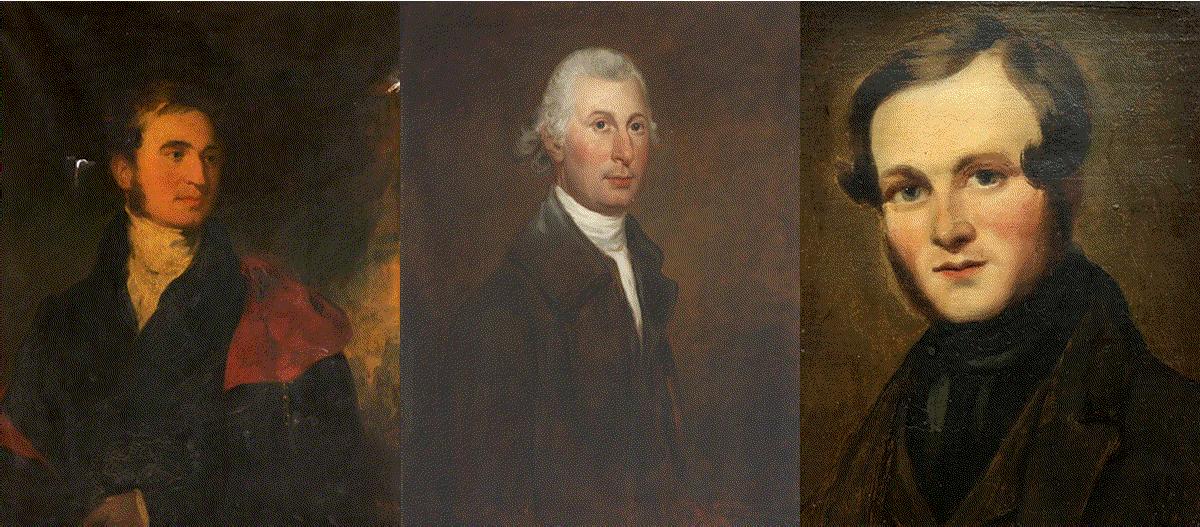

Self-portraits (L&R) and engraving by Henry Cousins after a portrait of Liverseege by William Bradley (Centre)

Moving Home

Henry's life changed radically when he was about thirteen years old, circa 1815, when he moved out of the family home to live with his uncle and aunt, John and Grace Green. Grace Mitchell had made a "better" marriage than her sister Elizabeth; John Green was a partner in the cotton spinning business Sandford and Green. While by no means one of the town's largest businesses, the Greens would have enjoyed a substantially more comfortable life than the Liverseeges who were described as "...of very limited means". The reason for his moving in with the Greens is generally ascribed to his father's harsh, or at least indifferent, treatment of the boy. It is easy to see how Edmund would have much sympathy for a boy whose interests and abilities were more artistic than practical. However, the timing suggests that there may also have been a pragmatic reason - the birth of his sister Mary in 1815 - which would have imposed further practical and financial burdens on the family. Moving in with the Greens seems to have been a win-win-win decision for all concerned: for Edmund and Elizabeth, the easing of the burden; for Henry, distance from an unsympathetic father and wider opportunities for his future; for the Greens, who had married in 1810 but remained childless, perhaps Henry would be the child they were unable to have.

Henry, despite his infirmities, was capable of attending school and spent some years at an academy run by Edward Dodds, described as being "in the garret of a house at the corner of Acton Street and London Road". His schooling appears to have begun when he was eleven, and so before his move to the Greens' home, which if correct suggests that any neglect did not extend to his education.

When about the age of twenty, Henry developed an interest in amateur theatricals and performed in a number of plays, most memorably taking the part of the nurse in Romeo and Juliet. His voice, which has been described as "reedy" possibly being an asset to the role. Acting, however, was not the field in which he was to make his name.

Becoming an Artist: Inn Signs and Portraits

It has been said that from an early age he was interested in drawing and drew constantly. Unfortunately none of his early efforts seem to have survived, so we have little opportunity to judge his abilities. Living with the Greens, this interest could be indulged and as it developed into painting in watercolours and then oils, he was supported and encouraged by John and Grace, even to the extent that John Green made a room available in his mill which Henry could use as a studio. Up to this time, he had received no formal artistic training.

Henry's first venture as a commercial artist fell short of "high art" and consisted of the execution of two signs for nearby public houses, the Saracen's Head in Rochdale Road at the junction with Church Street, ladnlord Mr. Williams, and the Ostrich. on the corner of Caroline Street and Wharf Street, publican, Samuel Kent. The former sign was painted on a stone slab "weighing several hundredweights". Whether this was brought to his studio or completed on site is not recorded. It was, though, generally regarded as a good representation. Henry used one of his uncle's employees, Samuel Sykes, as the model and is said to have received 10 Guineas for the work. The latter sign was less well received and has even been described as "bad". It is unlikely that Henry had ever seen an Ostrich but he could probably have found an engraving in a book. The Ostrich's clientele would probably have had no idea at all of what the bird looked like, so perhaps were not really in a position to criticise.

The Ostrich Inn c1896

(Manchester Local Image Collection)

The inn signs were really done as favours to friends of his uncle; his real commercial work at this time was as a portrait painter. Although he had previously had no artistic training, he is understood to have taken instruction in portraiture from another Manchester artist (John) Marshall Knowles around 1824. Little is known about Knowles. At this time he lived at 10 Meal Street (subsequently lost under the Lewis's building on the corner of Mosley Street and Piccadilly). In later life, he became an alcoholic and died died in Stockport on 22 May 1847 aged 50. Not one of his works is listed on the ArtUK web site, so we have no basis by which to measure his work.

His portrait painting spans the years 1822-1827. Only four examples of his portraits are known to survive, three of which appear below:

Thomas Whalley, William Wood (after George Keith Ralph) and Alfred Gomersal Vickers (his brother-in-law)

Liverseege's portraits have been described as "indifferent". Perhaps a better description would be "Good - for a provincial artist".

At least seven other portraits are known to have existed according to various biographical sketches produced after his death, but their whereabouts are unknown. Possibly they are in the hands of descendants of the sitters or perhaps lie in art gallery stores under the description "artist and sitter unknown" (of which ArtUK lists over 23,000 works). His sitters were largely local businessmen such as Bolton's Benjamin Hick who commissioned portraits of himself and his wife. Hick, an engineer and avid art collector, would become one of Henry's greatest patrons as his career progressed. It seems probable that there were many others, given the period for which he was employed on portraiture.

A Sociable Man

Henry was quite gregarious and delighted in the company of fellow artists. Manchester had a small and (in terms of its membership) unremarkable artistic community and Henry became friends with several of its members. He was a particularly close friend of Michael Pease Calvert, the son of Charles Calvert, both landscape painters and neither remembered today. Henry painted a portrait of Elizabeth, Michael's widowed mother, in 1827, possibly one of his last portraits. This was probably a gift to Michael rather than a commission. This portrait is now in the possession of the author after it recently appeared on the market. (For two fascinating videos showing the restoration of this painting by James Bloomfield, See Will this painting by forgotten Manchester Artist clean and Portrait comes alive after restoration)

Portrait of Mrs. Calvert

While Henry is known (or perhaps it should be "has been forgotten") as a painter, he was also an amateur poet and a member of the group of poets who met at the Sun Inn on Long Millgate, and which consequently had acquired the nickname of "Poets Corner". Other members of the group included John Critchley Prince, Samuel Bamford, Isabella Linnaeus Banks (the author of The Manchester Man), Ben Brierley, and John Bolton Rogerson. Little poetry appears to have been published in Henry's name but a humourous verse, "The Manchester Band O!" was reproduced in Ben Brierley's Journal of 18 July 1874.

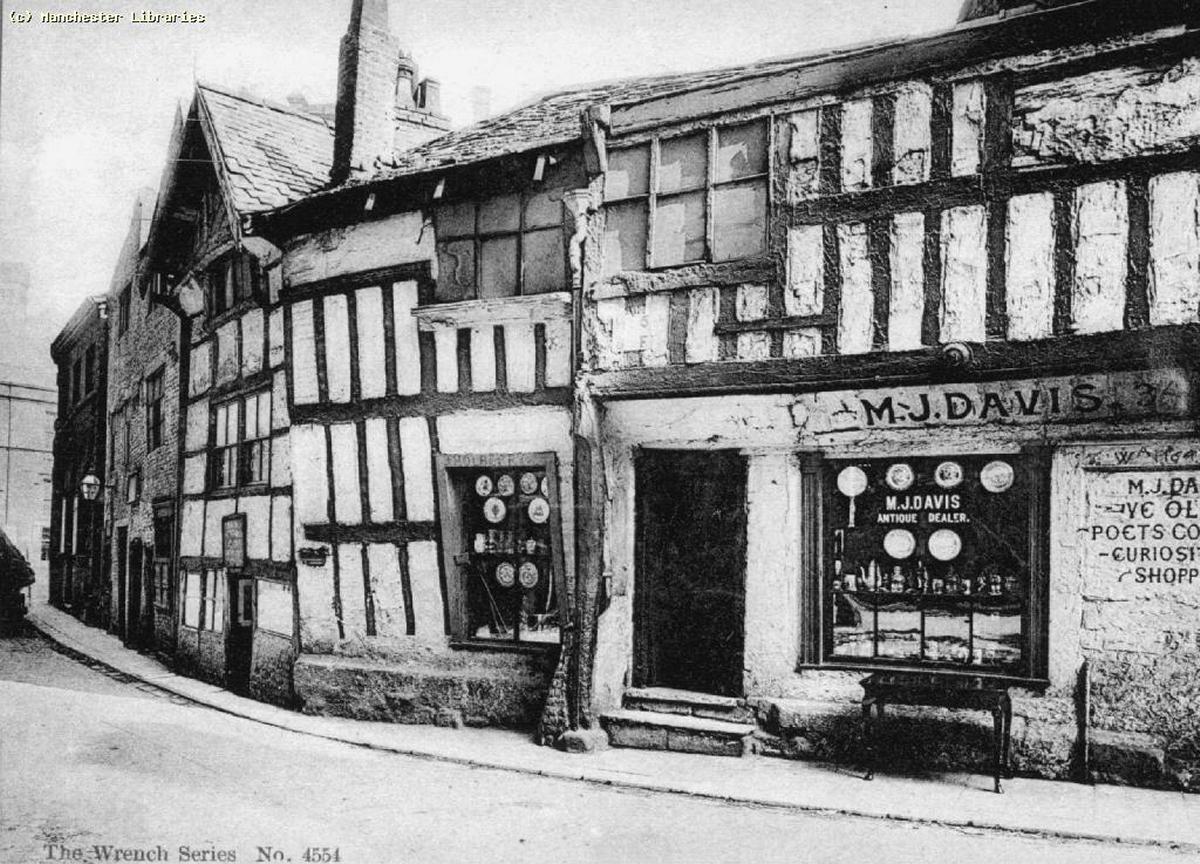

Poets Corner (the Sun Inn)

(Manchester Local Image Collection)

He also shared a workroom in Bradford Road rented by George Richardson and one of his friends. He would come around of an evening and give them instruction in drawing and painting and on occasions would read from some of his favourite books. Richardson would recall this arrangement in his pen-portrait of Henry published in Ben Brierley's Journal in 1874.

Changing direction: "Dramatic" Subjects

By 1827 Henry had had enough of portrait painting, which he found to be both tedious and poorly rewarded. While well-established Royal Academicians in London or Bath, with well-heeled aristocratic clients, might command fees in the hundreds of pounds, provincial portraitists might receive as little as £10 for a portrait. Henry's prices are said to have risen to 30 Guineas by the time he abandoned this avenue. Portraiture also offered little opportunity for creativity, so he painted his last portrait and from then on turned his attention to "dramatic" subjects in which he might let his imagination run wild.

His first known works in this new genre were exhibited at the Manchester Institution's first exhibition in 1827. His contribution consisted of three works which appear to have been in the style of the 17th century Italian artist Salvator Rosa. They were entitled "Banditti Attacking Travellers", "Banditti Carousing" and "A Robber on the Outlook" The location of the first of these is unknown, though a drawing exists which might be a study towards this subject. The second painting survives and was sold recently (as "Carousing Guards in an Interior") to a private buyer. The third is also missing, but what appears to be a preparatory sketch survives in the collection of the Whitworth Gallery. His interest in Rosa continued and at the time of his death a painting "Salvator Rosa among the Banditti" remained unfinished. These first exhibited works were well-received but did not readily sell. However, the critical response encouraged Henry to pursue this new path. By now, he clearly recognised the limitations of a provincial town and saw that the route to develop his skills - and a market for his work - lay in London.

Next Chapter

In the next part of this three-part blog, Henry makes three visits to London where he receives some instruction, makes the acquaintance of some famous artists, expands the variety of subjects for his paintings, paints prolifically, and becomes commercially successful. READ THE NEXT BLOG...

- Hits: 150