I Could Have Been a Judge...

I could have been a Judge, but I never had the Latin for the judgin'. I never had it, so I'd had it, as far as being a judge was concerned... I would much prefer to be a judge than a coal miner because of the absence of falling coal. (Peter Cook - Beyond the Fringe)

My Unhappy Relationship with Latin

I always had sympathy for Peter Cook when he blamed his lack of Latin for his failure to succeed in life because my own relationship with the language has not been a happy one.

In 1958 I was fortunate to win a scholarship to one of the country's oldest grammar schools. Latin was a compulsory subject for all pupils, I suspect more due to five centuries of tradition than its value in forging the new Britain which would be promised by Harold Wilson in his "white heat of revolution" speech five years later. I fear they regarded me as a disappointment. Over my first two years, my marks in Latin declined progressively until I achieved the accolade of "very weak" in my second year's report.. Mercifully, I was allowed to drop the subject when I entered the fourth form. Sixty-five years on, my alma mater no longer requires pupils to study Latin. Another change I would have welcomed was the merger with the Girls' High School - alas, also fifty years too late!

Unlike Peter Cook, I had no ambition to join the senior judiciary, nor to follow other careers in which Latin might have proved helpful such as becoming a mediaeval historian, even less entering the Roman Catholic priesthood. Latin would have little value in my chosen career in the world of telecommunications. But my nemesis was not slain, only sleeping soundly. When I began to research family history, it stirred in its sleep and began to awaken.

Once your family research has pushed back into the 18th century, odds are that you will run into records written in Latin. Latin was the usual language for legal documents up to 1733, when it was mandated that such documents should be written in English. But it is not only in legal documents where you will find Latin. Well into the 19th century you may come across gravestones or church memorials with Latin inscriptions and if your ancestors were Roman Catholics, the baptism, marriage and burial registers in which these key events in their lives are recorded will invariably be in Latin. You may even be unfortunate to find Latin used in an ancestor's will. So how do you go about understanding these records? Take Latin classes? Pay a translator? Give up and find a new hobby? The answer may simply be to learn enough to get by.

The Simple Approach

Travelling overseas, I soon learned that you could make a favourable impression and deal with the essentials with a very limited vocabulary and little knowledge of the grammar of the local language. My minimal dictionary consists of:

Hello; Please; Thank You; Where is?; Toilet; Beer.

Learn the right words and life is a lot easier. So, I offer:

- French: Bonjour; S'il vous plait; Merci (beaucoup); Ou est?; Toilette; Bierre

- Dutch: Goode Dag; Alstublief; Dank u wel; Waar is?; Het toilet; Bier

- Australian: G'day; Please; Good on ya sport; Where is; Dunny; Amber nectar

(Sources: French and Dutch phrase books; The Adventures of Barry McKenzie by Barry Humphries)

Memorial Inscriptions

What works for foreign holidays also works for records in Latin. You just need to know some key words. For example this memorial from Manchester Cathedral:

In spe beatae ressurrectionis, hic jacet Carolus MORETON, obit sexto die Februarij, anno post natam sultem mdccxxix aetatis suae xxix / nec Dorotheae uxor quae obijt xxviii Aug A.D. 1744, aetatis 41 / Carolus etiam filius natumaxs. qui obijt 10mo Junii A.D. 1747 aet 22 / et Thomas filius natuminis qui obijt 22do Julii A.D. 1759 aet 30

While the words which are not highlighted may have significance, the key words in the inscription are:

- hic jacet - Here lies

- obit - died

- sexto Februarij - sixth of February (see note on dates below)

- mdccxxix - 1729 (see notes on Roman numerals below)

- aetatis suae (or aet) - year of his/her age

- uxor - wife

- filius - son (filia if a daughter)

So, we can easily interpret this as the memorial to Charles (Carolus) MORETON who died 6 February 1729 aged 29; Dorothy, his wife, died 28 August 1744 aged 41, Charles their son died 10 June 1747 aged 22 and Thomas their son died 22 July 1759. There are still some words which we may not know, but the genealogical information was extracted with relative ease.

Notes on names: Surnames will generally be represented normally, but forenames will usually be translated into Latin and carry an ending which indicates whether the person is the subject or object of the sentence. For more information see Latin Forenames in our Reference Library section.

Note on Dates: Although dates may appear in a variety of formats, they are generally easy to interpret. Latin month names are recognisably similar to their English equivalents.

Roman Numerals: Converting Roman numerals into Arabic numbers is easily learned. A useful overview can be found at https://www.cuemath.com/numbers/roman-numerals/

Catholic Registers

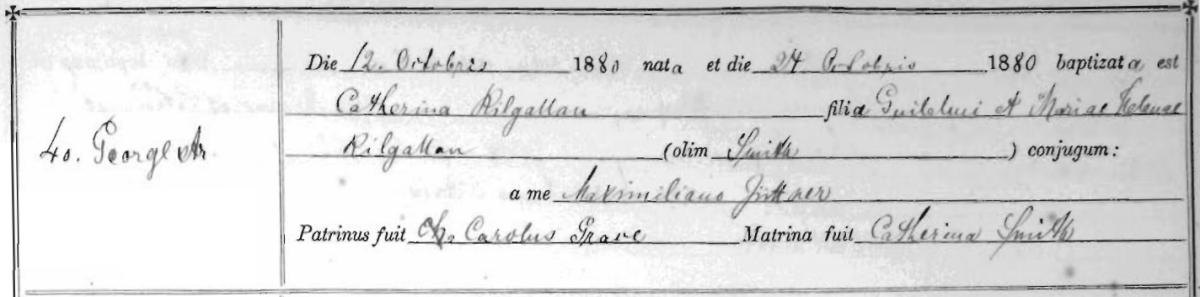

Another place you will encounter latin is in a Roman Catholic baptism, marriage or burial register such as the following baptism from the Church of the Holy Infant, Astley Bridge:

It is helpful that Roman Catholic registers generally consist of printed forms, so there is little scope for variations in format. Here again we need only know a few key words

- Nata - born

- et - and

- Baptizata - baptised

- Filia - daughter (filius if a son)

- Olim - formerly (the mother's maiden name)

- Conjugum - married (i.e. the parents wer a married couple)

- A me - by me (followed by the name of the priest)

- Patrinus fuit - the godfather was

- Matrinus fuit - the godmother was

You will occasionally come across further annotations in Latin. These may contain genealogically useful information but their translation and interpretation go beyond this simple overview.

Another Way...

If all of this still seems daunting, why not get a friend to help? My new friend ChatGPT was more than happy to oblige. ChatGPT is a free artificial intelligence application which takes Latin translation in its stride. Here is ChatGPT's translation of the memorial:

Me: Translate from latin to english: In spe beatae ressurrectionis, hic jacet Carolus MORETON, obit sexto die Februarij, anno post natam sultem mdccxxix aetatis suae xxix / nec Dorotheae uxor quae ibijt xxviii Aug A.D. 1744, aetatis 41 / Carolus etiam filius natumaxs. qui obijt 10mo Junii A.D. 1747 aet 22 / et Thomas filius natuminis qui obijt 22do Julii A.D. 1759 aet 30

ChatGPT: Certainly! The Latin inscription translates to English as follows: "In hope of blessed resurrection, here lies Charles MORETON, who died on the sixth day of February, in the year after the birth of our Lord 1729, at the age of twenty-nine. Also, Dorothy, his wife, who died on the twenty-eighth day of August, A.D. 1744, at the age of 41. Charles, their eldest son, who died on the tenth day of June, A.D. 1747, at the age of 22. And Thomas, the youngest son, who died on the twenty-second day of July, A.D. 1759, at the age of 30."

While (if you had not guessed already) I am not a sufficiently good Latin scholar to criticise the translation, it looks pretty good to me. Helpfully, it anglicises the personal and month names and converts the roman numerals into Arabic equivalents.

In Conclusion

If only ChatGPT had been around back in 1958! Maybe by now I would be a judge!

- Hits: 622